Palworld's special approach to game credits

A brief chat with Pocketpair's chief game director about crediting developers via a webpage.

Back when I started checking game after game to figure out where their developers and publishers place the in-game creator credits, I noticed a couple of surprising touches in Palworld. That’s the cute-monster-training-survival game from Tokyo-based Pocketpair that was the biggest thing last year and is still doing pretty well.

Palworld has a credits menu right up front, when you boot it up.

That’s common in many games these days, though not so much from studios based in Japan. Nintendo always—as best I can tell; haven’t seen an exception yet—puts game credits at the end. Capcom often does, too.

“Survival crafting games have no ending,” Pocketpair’s CEO Takuro Mizobe told me in Los Angeles way back in December, when I asked him about this. “It’s a very continuous game,” he said.

His point: There was no ending spot in Palworld where it made sense to roll credits. It made sense to just have a credits option up front.

When you click on Palworld’s main-screen “credits” button, something unusual happens.

In dozens of other big-budget and indie games that I’ve checked, that kind of menu option takes you to a scrolling list of credits.

In Palworld, it loads a web browser.

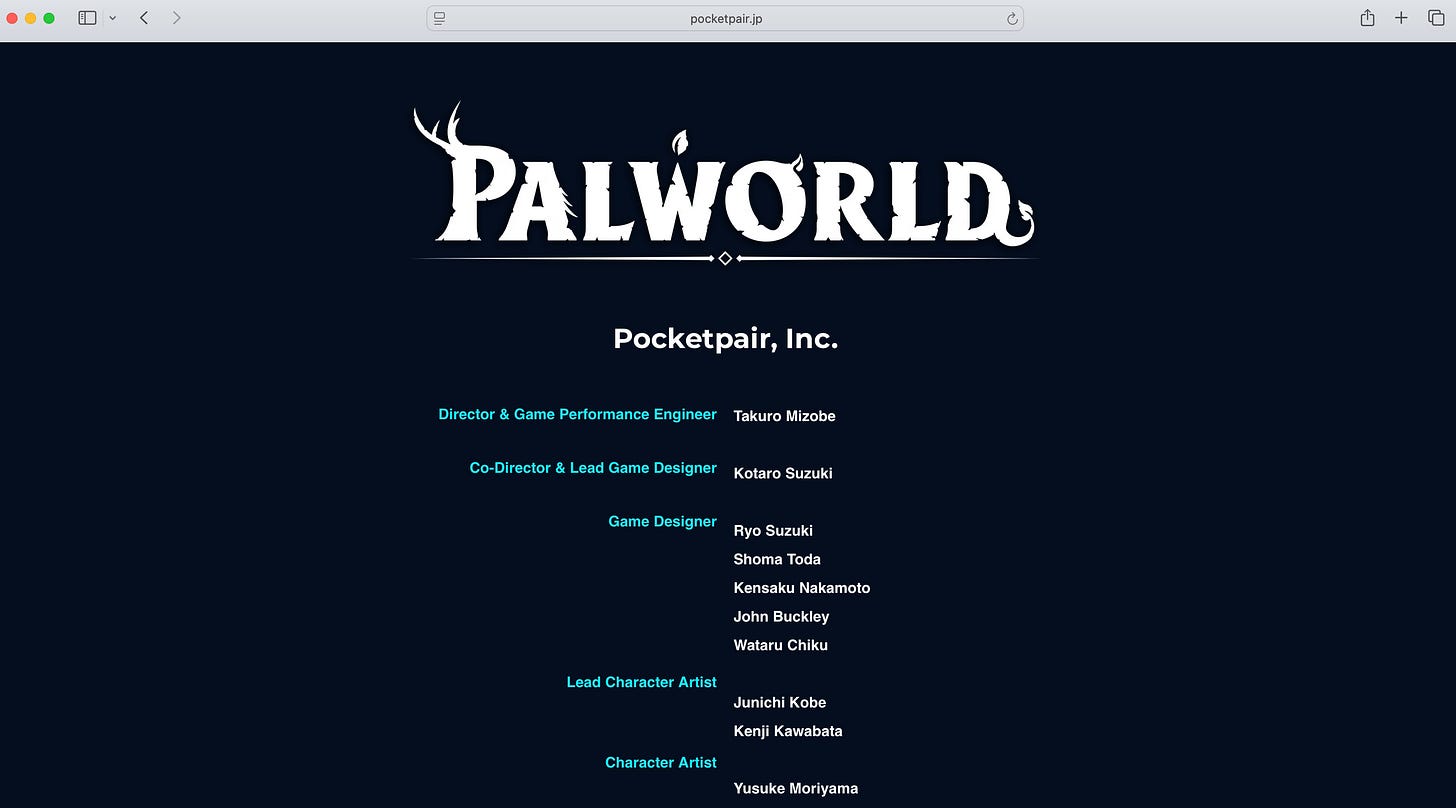

The browser loads this page. The official Palworld credits, you see, are simply a page on Pocketpair’s website.

“Making the credits is a bit tough, because we have to contact all of the developers and outsourcing partners [and get their names] and titles,” Mizobe told me. “Then we need time to prepare it. The website is easier to change.”

From Pocketpair’s perspective, he explained, they can keep the credits updated via a website, without having to update the actual game via PC and console patches. That’s clever.

I was curious if Mizobe and team had tried this approach before. To my surprise he said, no, because Pocketpair’s previous game, Craftopia, didn’t even have credits.

Why?

“Craftopia has no credits, because it’s a very small indie game,” he said. “Everyone knows me, and I know everyone. It’s a very small team.”

Heads up: Game File’s second annual summer sale is happening right now. Click here to sign up for 20% off the regular rate.

I didn’t initially follow Mizobe’s train of thought. But, as we chatted, I understood that, for him, credits in a video game aren’t really about providing information for the player to see who made the game. They’re about providing proof about who worked on the game. In the case of Craftopia, Mizobe was saying, there was no doubt who made it. The developers knew it. He knew it.

The Craftopia developers, Mizobe noted, all had indie gaming backgrounds.

By contrast, he said, some of Palworld’s staff “came from larger companies or the general industry.” They had the idea that there should be credits in the game, he said.

“It helps them with their next job?” I asked.

“Yes, yes” he said.

The credits, in other words, amount to a confirmation of the developers’ work experience and are useful when those developers seek work at other studios. (This is far from just a Palworld thing. It’s a common reason why developers around the world seek to be in the credits for video games.)

I wondered if Mizobe thought players also cared who made a game like Palworld and would be interested in the game’s credits.

He wasn’t sure.

A colleague of Mizobe’s standing nearby floated that it might be more of a Western thing to attach personalities to games. But, I countered, there are probably more big names attached to Japanese studios and franchises—Miyamoto at Nintendo, Sakaguchi back in the day on Final Fantasy, Harada on Tekken, Kamiya at Capcom and Platinum, Nagoshi formerly at Sega, etc—than there are big name developers in the West.

Perhaps that’s true, Mizobe allowed, but only at the most senior level. In Japan, he said, “even the industry guys only know the director name and producer name.”

Nevertheless, he said, whether credits are seen or not—whether players themselves want to see the list of names—”the developers are proud of making the games.”

This article is part of Game File’s ongoing efforts to answer the simplest of questions: Who made that video game you just played (or heard about)? I previously wrote about some game publishers’ reluctance to even say which studio is making a video game, how some of gaming’s biggest storefronts don’t tell you who developed the games they’re seling and about where 2025’s biggest games do or don’t place their in-game credits.

At Mountaintop Studios we had a specific credits policy outlining our approach to credits, objective criteria for who should be credited, etc. Specifying that the credits should be available without having to play the game is important making sure credits are available for everyone. Palworlds approach was excellent too since it could be accessible without even downloading the game while still being available in the game.

I never knew I would be so engrossed about the details of credit placements in games, thank you Stephen!