A buffalo at the Met, and a video game about stealing African art held by western museums

The upcoming heist game Relooted is an Africanfuturist fantasy, and it has already garnered some surprising support.

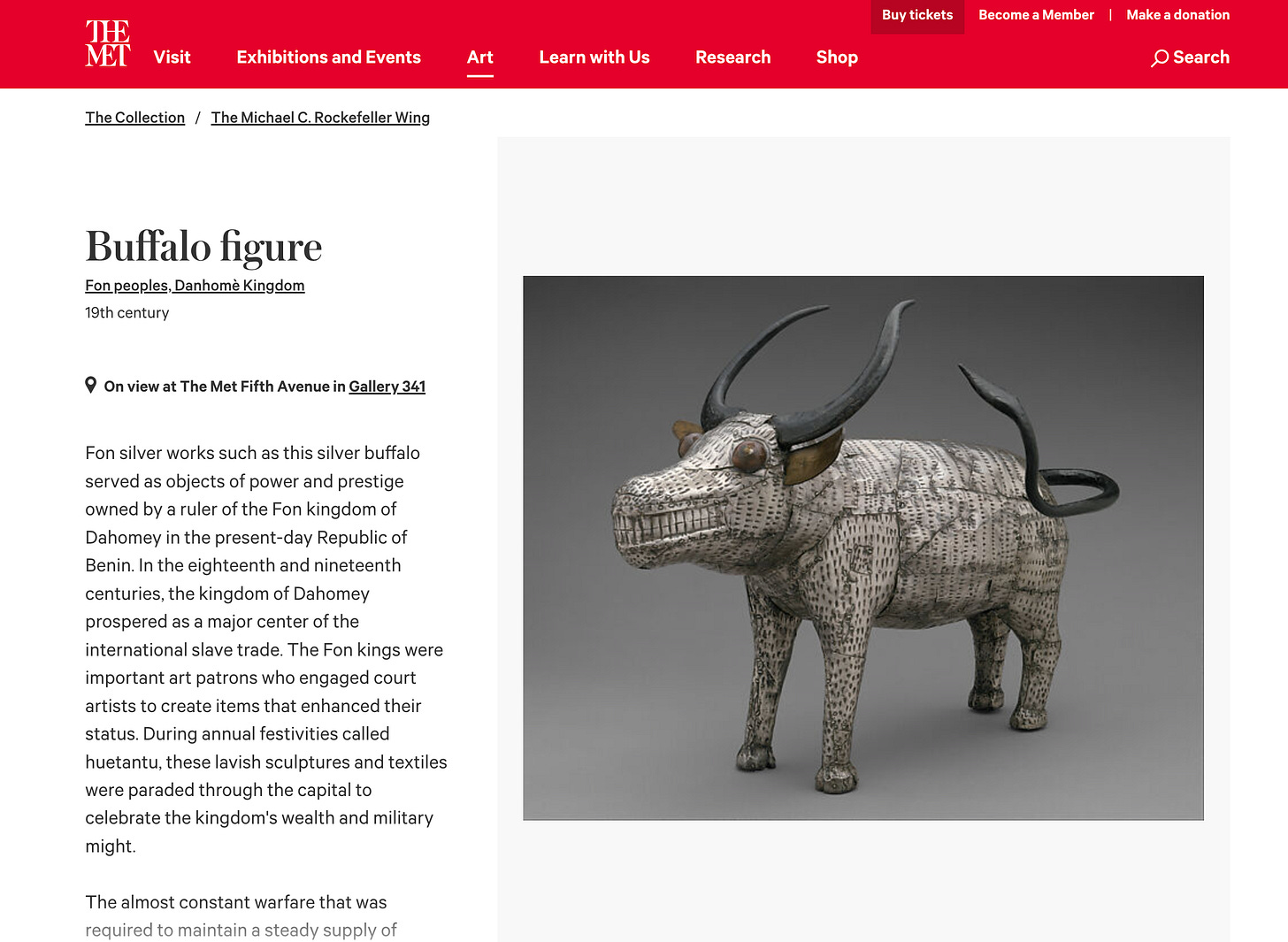

In the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the massive New York City cultural landmark on the eastern edge of Central Park, there’s a small silver figurine of a buffalo.

It was added to the Met’s collection in 2002, a gift to the museum from the collectors Anne d'Harnoncourt and Joseph Rishel, as the museum states, “in memory of Rene and Sarah Carr d'Harnoncourt and Nelson A. Rockefeller.”

The buffalo figure was crafted much longer ago, at least as far back as the late 19th century, by an artist in Dahomey, a region of Africa now part of the country Benin. It was “collected” by French colonial forces in the 1890s, changed hands since then and eventually was gifted to the museum.

Several weeks ago, the video game designer Ben Myres told me about this buffalo, as he demonstrated the game he is making with a team of developers from 12 African countries.

He was running a colorfully dressed character through a trap-filled set of hallways, as they tried to steal some art.

Relooted, as the game from studio Nyamakop is called, is a heist adventure about the repatriation of art and artifacts from Western museums, back to the lands of their origin.

“If I go to the Met, I can see it?” I asked Myres, regarding the buffalo.

“Yeah.” he answered.

“And if I play your game, I could steal it?”

“Yep,” he said.

Relooted is full of virtual versions of real-world artifacts that players can steal.

The game plays out in 2D, mixing careful strategy and precision execution. During a planning phase, players decide how their crew of righteous thieves will infiltrate and escape a heavily secured complex. In the action phase, they attempt to get in, grab the artifacts, and get back out.

Players of Relooted aren’t robbing the Met directly, nor other museums where the real objects are held.

Instead, in the fiction of the game, the museums of the world have agreed to return artifacts, largely from African nations, that has publicly been on display in the west, with the idea that that many such works were initially obtained through conquest and plunder. But the museums exploit a loophole in that process and hide the most precious items in private vaults full of traps and locked doors. Players break into those places to liberate the treasure.

“Repatriation of African artifacts has been a big thing in Africa for a long time,” Myres told me. “No one's really made a great non-violent heist game in the vein of Oceans 11, or anything like that. So we really wanted to explore how to do that.

Relooted has been in development for four years, Myres said, but he’s had the idea for seven.

He credits his mother, who was horrified by a visit to the British Museum in 2017. She’d felt “rage in her heart,” he said, over the Nereid Monument. It is composed of portions of a temple from what is now Turkey that were rebuilt inside the museum.

“She was like, ‘You should make this into a game,’” Myres said. “And I was like, ‘Moving a museum, a front of the building, out of a museum, I don't know how to make that fun.’ So we went smaller scale: African artifacts.”

Other stealable artifacts in the game include:

The Ishango Bone, a 20,000-year-old carved tool, likely used for mathematics. It originated in what is now the Democratic Republic of the Congo but is kept in a museum in Belgium, despite a requested return.

Vigango Statues, statues from Kenya held in museums and by private collectors from around the world. Some have been returned.

The remains of Prince Alemayehu, an Ethiopian prince whose remains are buried on the grounds of Windsor Castle. (In 2023, Buckingham Palace refused to return the prince’s remains to his descendants, saying the retrieval would affect other remains).

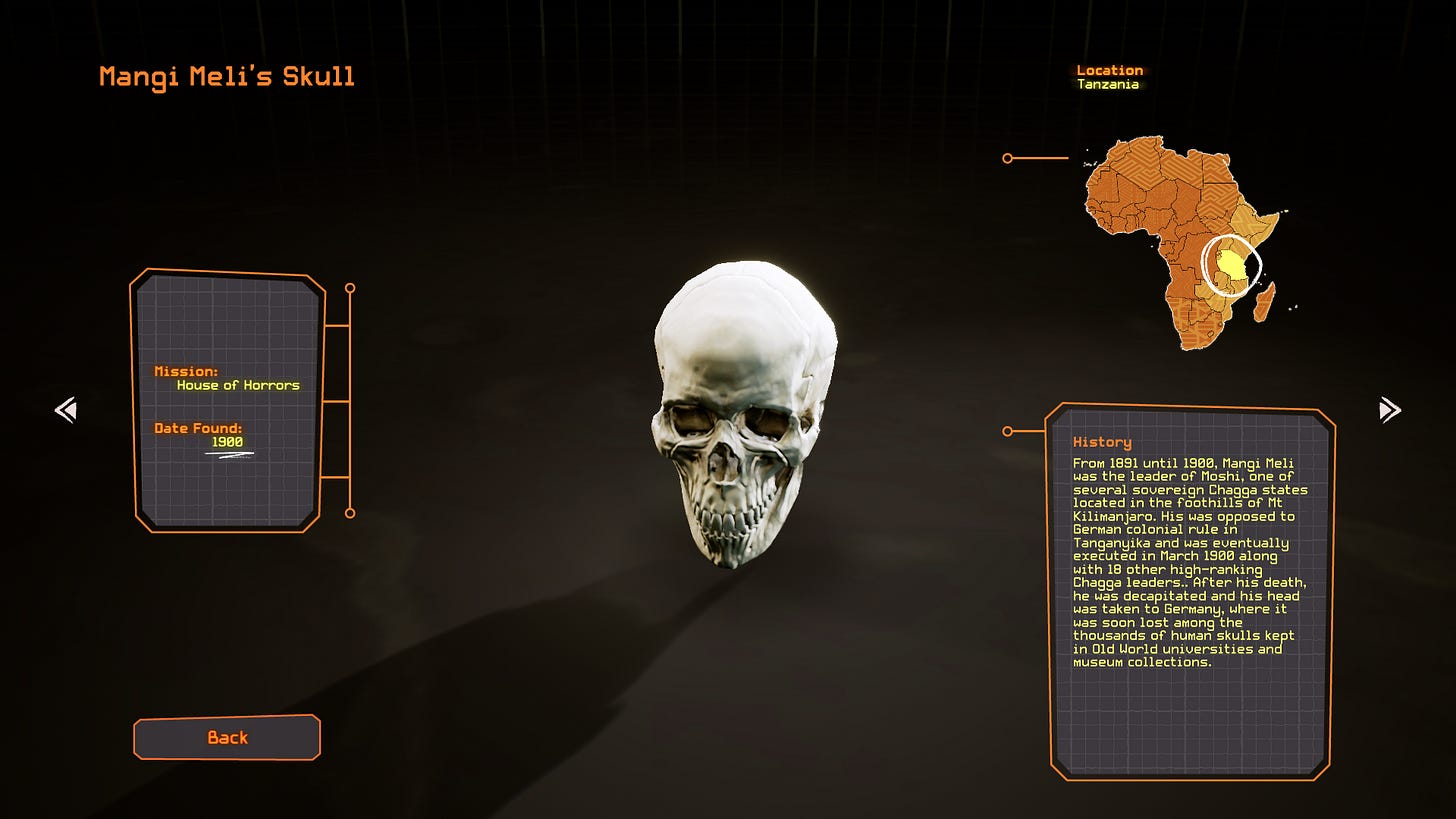

The skull of Mangi Meli, a chief in what is now modern-day Tanzania and who was executed by German colonizers. His skull—as with those of others—was believed to have been brought to Europe, though it is now lost.

Relooted’s levels include multiple artifacts, some held behind trickier traps. Players need to dodge lasers, leap past electrified barriers, breach locked doors, and race through fast-closing passageways.

“Relooted is about basically making your own speed run,” Myres said. “Each level is basically a broken Rube Goldberg machine of maybe 10 to 15 really simple puzzles that you're trying to solve in one go.”

As they reverse-plunder, players can scan each object and read more about it.

The objects that players steal in the game are then returned, in-game, to a virtual version of The Museum of Black Civilizations, a real four-story museum for art that opened in Dakar, Senegal in 2018.

“It's a real place, and it's quite big,” Myres said.

“But the story goes that half of it is deliberately left empty because they're waiting for all the artifacts to come back from the West.

“So you do have this museum in Africa that literally is empty, and at the end of the game is full.”

Regarding that specific buffalo

Myres can’t say with 100% certainty that the buffalo figurine in the Metropolitan Museum of Art was looted 130 years ago.

But it is, to him, a reasonable inference.

The Met officially states that it was “Collected in Abomey, Republic of Benin, by the French colonial forces, 1894.” Abomey was part of the Dahomey kingdom.

“It places it in Abomey at the time documented looting happened,” Myres told me over email, pointing to some of the historical record of the time. “Also states it was taken by 'French colonial forces' who are documented to have taken other loot.”

He added:

“In the cultural context of the artifact itself, these animal figures were made by the royal guilds as power figures exclusively for Kings. They were only displayed and placed in the palace of Abomey. They wouldn't have been traded or moved elsewhere.

“So while we don't have specific documented evidence of this artifact being looted, it was collected in a time and place where all the other documented looting occurred, and wouldn't have been found or gifted elsewhere (there was no functioning local government to do that anyway). “

(A recent documentary called “Dahomey” focuses on the repatriation of looted art.)

Over the years, The Metropolitan Museum of Art has returned some art to foreign nations. On its website, it has published a “partial list” of dozens of artifacts it has repatriated to Nepal, India, Cambodia, Nepal and Egypt.

The Met says it works hard to understand the origins of the art in its collection and is open to new information.

“The Museum prioritizes continual research into the past ownership of works across our collections, and has made significant investments in accelerating this effort, spearheaded by the largest provenance research team in the world,” a spokesperson for the Museum told me.

They rep noted that the Met “has a long track record of working collaboratively when questions have arisen about an object’s prior history.”

About the buffalo figure, though, no other information appears to be available than what the Met has already stated. The French military “collected” it. It passed through collectors. It was gifted to the museum.

Myres told me: “I too would like more specificity about this object's provenance path.”

Since Relooted was shown at the Summer Game Fest event in June, Myres says the game has drawn a surprising amount of interest and support.

He’s heard from Western museums who have asked if they’d like to feature their objects in the game, even offering to help with 3D scans. “It’s quite cool that the workers of the institutions we are critiquing really get the game,” he said.

He’s fielded mainstream media interest and even heard from video production companies. Some would like to turn Relooted into a TV show or a film.

The game, though, will come first. Myres and his team are aiming to release it in the next 12 months, and have announced it for PC and Xbox.

This is a brilliant premise for a game! How about a take where it's Black Panther, or someone from Wakanda, doing it from real life museums, and repatrioting the artifacts as a way to apologize for Wakanda not having shared their tech/science/knowledge with the rest of Africa?